Collecting Folklore Wasn't Always Easy for the Early Folklorists

Plus, I’ve been working to strengthen the folklore in the novel I’m revising

Hello!

Last week, I took a day trip up to Los Angeles with my son, one of his friends, and my daughter. We primarily went to visit the Getty Center, although we also stopped at The Grove to eat and shop.

I always enjoy visiting the Getty as it offers a range of art (from medieval to contemporary), plus it has unique architecture and beautiful gardens. And the views! You can see so much of LA from where the museum is perched on the hillside. Here are a few photos. :)

Behind the Scenes: Strengthening the Folklore

Because of … well, life … I didn’t get to do as much creative writing this past month as I had wanted to do. I did work a bit on strengthening the folklore in the novel I’m revising. I want to be consistent with the way I’m portraying the faeries and folkloric creatures, as well as the folklore that I’ve woven in. I’ve been documenting the folklore I’m using and then checking my manuscript against that. When needed, I’ve made revisions to clarify or be more consistent in my novel.

Exploring Folklore: Collecting Folklore Wasn't Always Easy for the Early Folklorists

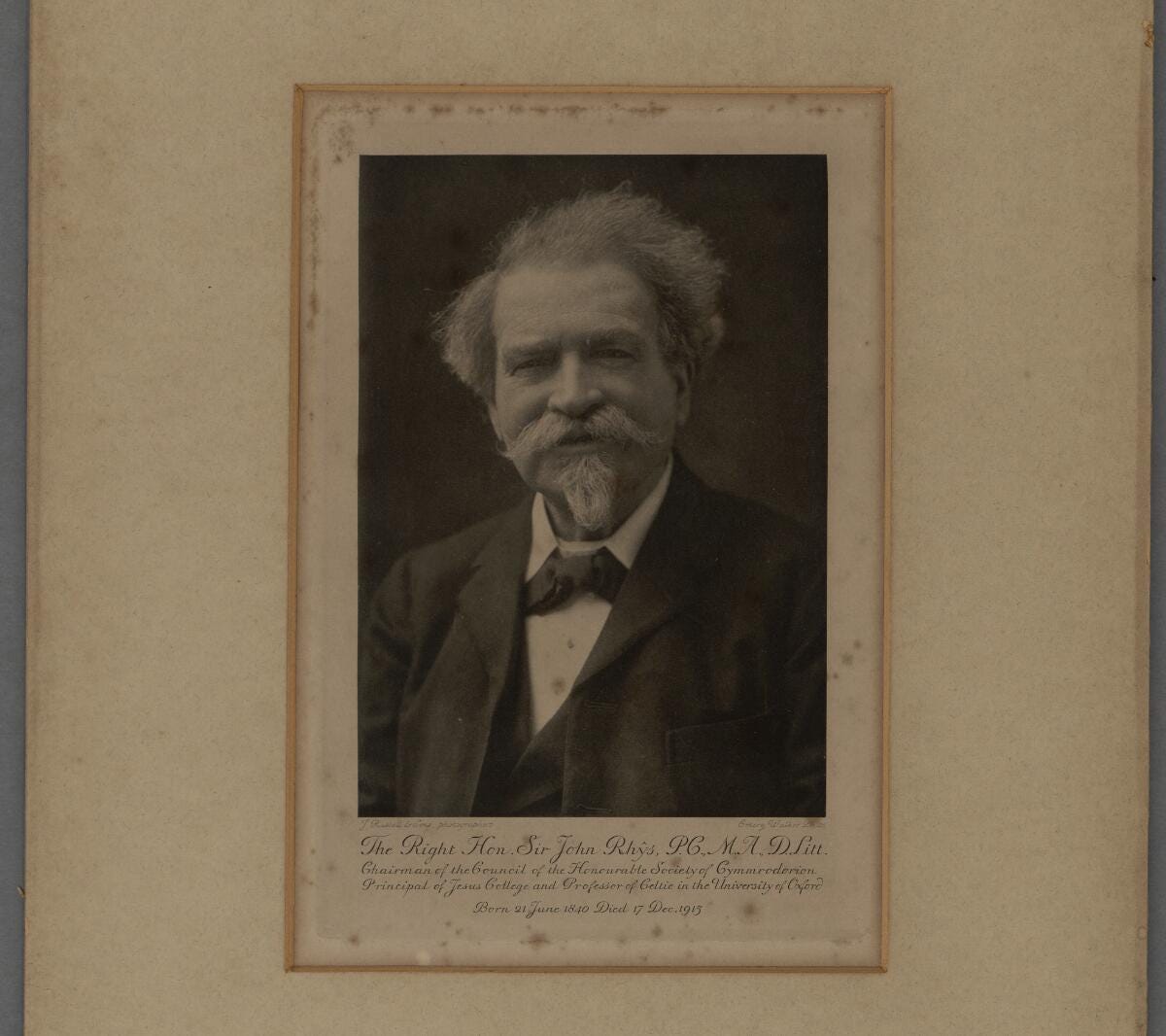

One of the first books of folklore that I added to my collection was Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx by John Rhŷs. It is a two-volume study, and toward the end of the book (in volume 2) Rhŷs includes a chapter called “Difficulties of the Folklorist.” In it he describes challenges he often faced while collecting folklore and while writing his book.

I have always found this section of Rhŷs’ book intriguing, so I read through it again, taking notes. I then looked through other collections of British and Celtic folklore published in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to see if they covered any of the same themes as Rhŷs. I discovered that many folklorists discussed similar topics and feelings, often in the prefaces or introductions to their books.

So I thought we might take a behind-the-scenes look at early folklore work to learn about some of the challenges folklorists encountered and how they overcame them.

A Strong Focus on Collecting Folklore

One of the primary goals of folklorists in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was gathering as much folklore as possible. John Rhŷs highlights the importance of this in his book and explains why the collection of folklore is valuable:

… we want all our folklore and superstitions duly recorded and rescued from the yawning gulf of oblivion, into which they are rapidly and irretrievably dropping year by year, as the oldest inhabitant passes away.

Other collectors of folklore shared similar concerns. In Lancashire Legends: Traditions, Pageants, Sports, &c. With an Appendix Containing a Rare Tract on the Lancashire Witches, &c. &c. by John Harland and Thomas Turner Wilkinson, the first paragraph of the preface is devoted to the worry that “popular legends and traditions are rapidly disappearing from the fireside literature.” Several reasons for this are offered:

Some of them pass away with the ancient mansions to which they were attached ; others die out with the individuals who were wont to repeat them orally to their descendants ; and not a few have become modified by the changes which have taken place in our social relationships to each other. Elementary education, also, is doing its work slowly, but surely, and with the spread of correct information amongst the masses, much of our popular superstition will cease to exist.

By gathering and recording folklore, tales, traditions, and legends, folklorists hoped to preserve this information in a scholarly manner for future generations. Additionally, these folklore collections often pertain to a specific group of people, county, or country, as folk traditions often vary with location.

I did notice that folklorists interested in collecting folklore tried to keep their focus on gathering and documenting. They occasionally share observations, but they seem content to leave the making of comparisons and determining meaning to other scholars who specialize in comparative folklore.

Methods of Collecting Folklore

Several methods of collecting folklore were available to the early folklorist, including oral interviews, exchange of letters, and other books of folklore. But while these methods may seem straightforward, they often came with challenges.

In his book, John Rhŷs emphasizes that it was important to him to accurately record information given to him by interviewees without altering the language. Even if the spelling or grammar wasn’t perfect, he felt it best to keep the informant’s language as close to the way it was given to him as possible.

Along the same lines Elias Owen, author of Welsh Folk-Lore: A Collection of the Folk-Tales and Legends of North Wales, states that while most of the information he gathered from oral interviews was shared with him in Welsh, he tried to be a faithful translator. He explains that he has provided literal translations “without embellishments or additions of any kind whatsoever.”

There also was a clear preference to obtaining folklore from people rather than other books. In The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries, W. Y. Evans Wentz explains that he desired to better understand “what the Celtic people think of fairies,” not what scholars thought of faeries. Celtic people were the authority on the subject. However, to do so required much more effort. To speak with people, folklorists often traveled on foot or by horse to collect folklore.

Evans Wentz traveled in Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Brittany, the Isle of Man, and Cornwall in order to gather folklore first hand. He writes:

Many of the most remote parts of these lands were visited; and often there was no other plan to adopt, or any method better, or more natural, than to walk day after day from one straw-thatched cottage to another, living on the simple wholesome food of the peasants. Sometimes there was the picturesque mountain-road to climb, sometimes the route lay through marshy peat-lands, or across a rolling grass-covered country; and with each change of landscape came some new thought and some new impression of the Celtic life, or perhaps some new description of a fairy.

As someone who loves to walk and think about folklore, this fascinated me. He explains that he traveled for over three years, and that it had a profound effect on him.

Challenges Encountered While Interviewing People

In his book, John Rhŷs mentions that when it came to speaking with or writing to individuals in order to collect stories and folklore, he “had difficulties in abundance to encounter.” Some folks were rather shy to talk on the subject. Others worried that they might be portrayed in a negative manner. He also explains that for a variety of reasons, folklore was not always taken seriously. As a result, people who were familiar with superstitions and traditions were afraid to share their knowledge for fear of being ridiculed.

The folklorists did have a few strategies available to them to offset these challenges. Elias Owen notes that while he preferred to acknowledge the names of his informants in his book, he always respected their privacy if they asked to be anonymous in print.

And John Rhŷs and W. Y. Evans Wentz appeared to be rather skilled at making people comfortable in opening up to talk about faeries and folklore. They had a similar approach, perhaps because Evans Wentz studied under Rhŷs for a year before he began traveling through Celtic countries to gather folklore. Evans Wentz gives a lovely example of this in his book:

Our next witness is Bridget O’Conner, a near neighbour to Patrick Waters, in Cloontipruckilish [my educated guess is that this is a misspelling of Cloontyprughlish]. When I approached her neat little cottage she was cutting sweet-pea blossoms with a pair of scissors, and as I stopped to tell her how pretty a garden she had, she searched out the finest white bloom she could find and gave it to me. After we had talked a little while about America and Ireland, she said I must come in and rest a few minutes, and so I did; and it was not long before we were talking about fairies: ….

Evans Wentz additionally felt he was particularly suited for interviewing Celtic people in that he was partly Celtic by blood, but born in America. He felt this gave him a unique perspective and “privileged” access to the Celtic world.

Determining Fact From Fiction

Several of the folklorists mentioned a frustration they had occasionally encountered when examining other works of folklore. In their pursuit of authentic folklore, they did not hold with careless writers who wrote about folklore in a “hopeless fashion.” John Rhŷs gives several examples of poorly presented folklore which include not understanding the Welsh language enough to translate accurately and not giving specific names of natural features (like names of lakes).

Rhŷs also describes an occasion where an author combined stories and legends to make a new folktale. While this might be condoned in fiction writing, it is not acceptable practice if the story is being touted as a true folktale.

John Harland and Thomas Turner Wilkinson also bring up this topic. They mention an author who apparently invented some traditions and erroneously assigned a tradition to the wrong locale. This prompted them to declare that in their book “… the popular legend in every case has been sought to be preserved, without any attempt to add the slightest embellishment, much less to rear a superstructure of invented fiction upon the crumbling foundations of a genuine tradition.”

This is something that I’ve come across in my own research. When I was taking notes for my post on the birds of Rhiannon, I encountered some folklore about the birds that had been widely quoted and upheld by early scholars, but was later determined to be fabricated and not authentic medieval folklore. I was glad to learn of this inaccuracy before accidentally using inauthentic folklore in my piece.

Efforts to Defend and Support the Study of Folklore

In the later portion of the nineteenth century, folklore began growing in interest, but it still hadn’t found solid footing. Folklore studies had only begun in the early nineteenth century, and it was considered a young subject working to earn its place within the scholarly community. Consequently, publishers were sometimes hesitant to publish folklorists’ collections. I was surprised to discover that several of these authors used a subscription model in order to generate interest and secure a publisher.

Similar to how modern authors might use Kickstarter to crowdfund a book, folklorists would gather subscribers so that the publisher would be assured of a certain amount of sales. In this way publishers would be more apt to take on a folklore title. The subscribers’ names would often appear in the book as a way of thanking them. Elias Owen explains in the preface of his book:

Before undertaking the publishing of the work, it was necessary to obtain a sufficient number of subscribers to secure the publishers from loss. Upwards of two hundred ladies and gentlemen gave their names to the author, and the work of publication was commenced. The names of the subscribers appear at the end of the book, and the writer thanks them one and all for their kind support. It is more than probable that the work would never have been published had it not been for their kind assistance.

This type of subscription model was needed for both Owen’s and Harland and Wilkinson’s books. Evans Wentz notes, though, that by the time his book was published in 1911, there had “come about a complete reversal of scholarly opinion” with respect to folklore. Rhŷs, too, does not mention a need for subscribers. Indeed, during the twentieth century folklore studies became recognized as a discipline, like history or anthropology, which most likely reduced the need to obtain subscribers.

As I wrote and revised this post, I realized that many of the challenges faced by folklorists of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries still resonate today. I’m sure modern researchers in the social sciences might relate to the efforts of these early folklorists.

As ever, thank you for subscribing and reading.

All the best,

Steph

PS: Do you enjoy visiting museums, too? Do you have a favorite one? I’d love to know. :)